We’ve reached step 5 of 7 in the music editing process and it’s one of the most fun and anticipated steps: The Scoring Session.

We’ve reached step 5 of 7 in the music editing process and it’s one of the most fun and anticipated steps: The Scoring Session.

This is the day when the composer gets to realize all of his/her hard work and hear what, until now, has only existed in their imagination (although more and more these days, composers work with synthesizers to produce working samples of the cues – known as “mockups” – that help them to rely less and less on pure imagination).

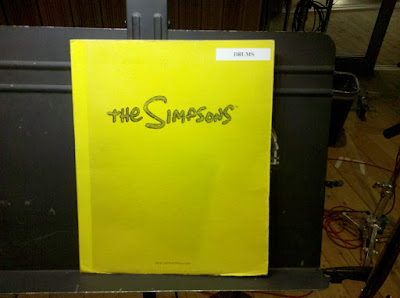

On Friday, August 19, 2011 we scored THE SIMPSONS episode NABF16 “The Falcon and The D’ohMan”. This is episode #487 in our long, storied history and is scheduled to air as the season premier of season #23 on FOX on Sunday, September 25, 2011.

“Score” can be used as a noun or a verb in the film music biz. As a noun it means the music that accompanies the action in a film or TV show; as a verb it means the action of recording said music on a special stage. This stage has been fitted with not just recording equipment, but also video or film playback equipment so that the cues can be recorded while watching the picture, then played back while watching the same picture and listening to the dialog to check that the music properly fits and compliments the scene. All music can be recorded anywhere from a concert hall to a cathedral to a bedroom. But the ability to record and playback music with picture and dialog is what separates a recording studio from a scoring stage.

One other very important difference between recording and scoring is that most cues are scored while the musicians listen to a “click track” in their headphones while they play. A click track is the film music term for a device that all you piano students remember from childhood as a “metronome”. As I discussed in a previous post, the composer uses the picture and the breakdown notes to calculate the tempo and the number of beats needed in a cue to cover the scene as spotted. ALERT! MATH AHEAD! For example, if the cue is supposed to be exactly 1 minute long, and the composer chooses to write the cue at a metronome mark of 60 beats-per-minute, then there would be exactly 60 beats in the cue (1 beat-per-second). If the composer chose a tempo of 120 beats-per-minute, then there would be 120 beats in the cue (2 beats-per-second), and so on. So that the orchestra can meet this rigid timing, a click track of the chosen tempo is played to the all the musicians on headsets. Many conductors have a very keen sense of tempo, but it is very difficult to lead a large orchestra at a precise tempo over a prolonged period of time.  In the good ol’ days, a conductor would mark up the score to indicate which bar of music should occur at a specific timing. Then they would use the stopwatch that was built into the podium. Keeping one eye on the score and one eye on the stopwatch, they would know if they arrived at the destination bar at the correct timing. The stopwatch in the photo is permanently attached to the podium on the Newman Stage, but hasn’t gotten much use these days thanks to computers and click tracks. The use of a click track ensures precise timing and helps the orchestra members to play together with greater accuracy. And don’t forget, there are numerous moments during the cue that need musical emphasis and the composer has meticulously mapped out those moments. (e.g., at 20 seconds in the cue the lovers kiss, at :45 seconds, the bedroom door bursts open, etc.) It’s not only important that the overall length of the cue be accurately met, but those internal “hits” are every bit as important.

In the good ol’ days, a conductor would mark up the score to indicate which bar of music should occur at a specific timing. Then they would use the stopwatch that was built into the podium. Keeping one eye on the score and one eye on the stopwatch, they would know if they arrived at the destination bar at the correct timing. The stopwatch in the photo is permanently attached to the podium on the Newman Stage, but hasn’t gotten much use these days thanks to computers and click tracks. The use of a click track ensures precise timing and helps the orchestra members to play together with greater accuracy. And don’t forget, there are numerous moments during the cue that need musical emphasis and the composer has meticulously mapped out those moments. (e.g., at 20 seconds in the cue the lovers kiss, at :45 seconds, the bedroom door bursts open, etc.) It’s not only important that the overall length of the cue be accurately met, but those internal “hits” are every bit as important.

This photo shows the special mixing console that sits on the FOX NEWMAN Scoring Stage for the purpose of handling and sending the click track and the “cue mix” (a blend of the live orchestra or just specific instruments as they are recorded) to the musicians’ headphones.

This photo shows the special mixing console that sits on the FOX NEWMAN Scoring Stage for the purpose of handling and sending the click track and the “cue mix” (a blend of the live orchestra or just specific instruments as they are recorded) to the musicians’ headphones.

In this photo, you can see the headphones perched atop the music stands prior to the musicians arriving at the Newman Stage.

In this photo, you can see the headphones perched atop the music stands prior to the musicians arriving at the Newman Stage.

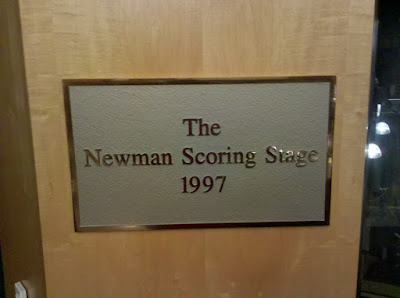

SIDEBAR: The Newman family has a long history in Hollywood film music. Alfred Newman was the music director of 20th Century Fox for over twenty years starting in 1940. He composed the well-known “Fox Fanfare” that you hear at the start of every Fox film and at the end of every episode of THE SIMPSONS. His brother Lionel, a fine composer in his own right, became the director of television music for Fox in 1959. Alfred’s sons David and Thomas are highly respected and sought-after composers having scored nearly 200 films between them. His nephew is Randy Newman of “I Love L.A.” fame and has also won two Academy Awards for his film scores. Because of this great legacy and the family’s long-time involvement with Fox, when the scoring stage was redesigned and refurbished in 1997, upon its reopening it was christened: The Newman Scoring Stage

SIDEBAR: The Newman family has a long history in Hollywood film music. Alfred Newman was the music director of 20th Century Fox for over twenty years starting in 1940. He composed the well-known “Fox Fanfare” that you hear at the start of every Fox film and at the end of every episode of THE SIMPSONS. His brother Lionel, a fine composer in his own right, became the director of television music for Fox in 1959. Alfred’s sons David and Thomas are highly respected and sought-after composers having scored nearly 200 films between them. His nephew is Randy Newman of “I Love L.A.” fame and has also won two Academy Awards for his film scores. Because of this great legacy and the family’s long-time involvement with Fox, when the scoring stage was redesigned and refurbished in 1997, upon its reopening it was christened: The Newman Scoring Stage

THE SIMPSONS typically employs a 35-piece orchestra to score the episodes. This includes a string section of 17 players, 4 woodwinds, 7 brass, 2 keyboards, 2 percussionists, 2 guitars, and harp. This can vary slightly from episode-to-episode depending on any special instrument requirements. When Selma traveled to China to adopt a baby, we had many authentic Chinese instruments; when the family traveled to Australia, we added a didgeridoo; if an episode centers around Apu, we will usually include extra Indian instruments. For NABF16 we used the standard orchestra.

A scoring session for THE SIMPSONS is booked for 3 hours. That is the minimum call for scoring musicians according to the union rules. (There are all sorts of different scales and rules for different music gigs: symphony orchestra, dance band, CDs, etc.) A scoring musician will be paid for 3 hours whether or not their services are needed for the full 3 hours. With this rule in mind, the music is recorded not in the order that the cues will appear in the episode but starting with the cues requiring the largest number of players first, then gradually fewer and fewer players. This way, when certain players have played all their music for the particular session, they can be dismissed and will be paid for 3 hours. Then if we need to go beyond 3 hours and into an overtime situation, we will be using maybe only 2 or 4 or 5 players, rather than 35. Sometimes we need to hire a musician for only 1 or 2 cues. They come in, play for 10-15 minutes, are dismissed and get paid the 3-hour minimum. Nice work if you can get it!

Click here to see the orchestra breakdown and recording order as prepared by JoAnn Kane Music Service and our music librarian Joe Zimmerman. You can see on this breakdown the order of the cues, the number of musicians needed for each cue, and what instruments will be playing on each cue.

The composer notates the score for all the instruments, writing on large score pages with twenty or more separate lines of music. The score pages are then sent to the music library where copyists extract each line of the score and create separate parts for each musician. This job used to be done by hand, using special pens and inks on special paper. Now, as with so much in the world today, the parts are entered into a computer and then printed using a laser printer. This way changes can be made more easily, parts can be sent from the library to the scoring stage via the Internet, and an entire score can be transported (the files anyway) on a thumb drive. The parts are still printed on paper and put into folders for each musician, so there is a lot of organizing and tracking that goes on, all under the watchful eye of the librarian. There are already prototypes for electronic sheet music tablets (think of an iPad being mounted on a music stand) that would do away with the need for paper. The tablets could even be synchronized to timecode to know when to “turn the page”, or to flash the screen alerting a player that their turn to play is coming up soon.

The hiring and managing of the orchestra is all handled by our contractor Murray Adler. While many of the musicians in our orchestra could be considered regulars, the truth of the matter is that there are no long-term contracts for musicians anymore. Each musician is treated as an independent contractor, hired for the specific session, then “laid off” as soon as they are dismissed from that session. Many of our players have played in various orchestras in different shows with Alf for over thirty years. After Alf reviews the spotting notes after the spotting session, he calls Murray and they discuss what the orchestra for that episode needs to be. If it’s just the standard 35, then Murray knows whom to call. If we need that specialty player (didgeridoo, bagpipes, sitar, Theremin) Murray finds the appropriate player and hires them. The musicians who bring large instruments (cello, bass, keyboard/synth racks, percussion) are entitled to use a cartage company to ship their gear. Murray handles the invoicing of the cartage companies. Do we need to rent a special instrument? Murray is on that one, too. Murray, like many contractors in the biz, are former studio musicians themselves. For the first fifteen years or so of THE SIMPSONS Murray was our first-chair violinist, also known as the concertmaster.

When THE SIMPSONS began in 1989, we recorded the music on analog 4-track tape. We used three of the tracks for the music and the fourth track was used to record the timecode. By recording the timecode onto a track, you could play the music back in sync with the picture using special synchronizing devices. For the three music tracks we recorded a LEFT channel, a RIGHT channel and a CENTER channel. We would use the CENTER channel to isolate any instrument(s) so we could raise or lower the instrument(s) in relation to the orchestra. If the special instrument got in the way of the dialog, we could lower it without affecting the rest of the orchestra. Back then the show was broadcast in what is known as DOLBY Surround, a 4-track playback method with one of each Left, Center, Right, and Surround speakers. Most homes in 1989 did not have DOLBY Surround playback capability so you would just hear the sound in mono or stereo out of your built-in TV speakers.

As we moved on into the late 1990s, we switched to digital 8-track recording. Mind you it was still on tape, but digital nonetheless. With eight tracks, we now recorded the orchestra in four stereo sections – Strings with Harp, Brass and Woodwinds, Percussion, Keyboards. Now each section could be raised or lowered independently and gave us greater mixing flexibility. For a brief time in the early 2000s we started recording on a digital 8-track disk recorder. Everything was the same except we now recorded to hard disk instead of tape. It wasn’t into a computer quite yet, it was a stand-alone disk recorder.

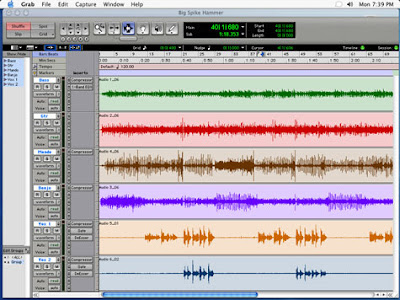

In 2004 we finally switched over to recording into a computer running Pro Tools. Pro Tools has become the de facto standard for all TV & film post production audio editing and mixing. While we could record as many as 192 tracks with Pro Tools, we’ve decided on a very manageable track count. We record 15 tracks for the orchestra – six stereo tracks for Strings, Keyboard 1, Keyboard 2, Brass + Woodwinds, Percussion, and Surrounds plus three mono tracks for Harp, Low Bass, and Miscellaneous (the miscellaneous track takes the place of the Center channel we used to record back in 1989).  The score is recorded “live to disk” meaning that although we could remix the music after recording using all the separate tracks, for the most part we don’t. We will do a few rehearsal passes of the cue so that our Music Scoring Mixer Rick Riccio can get the proper balances, and Alf Clausen can approve what he hears. Next, we record a few takes until the performance is perfect, then we move on to the next cue. When you have, on average, 25-30 cues to record in three hours, you can see why we don’t have time for remixing.

The score is recorded “live to disk” meaning that although we could remix the music after recording using all the separate tracks, for the most part we don’t. We will do a few rehearsal passes of the cue so that our Music Scoring Mixer Rick Riccio can get the proper balances, and Alf Clausen can approve what he hears. Next, we record a few takes until the performance is perfect, then we move on to the next cue. When you have, on average, 25-30 cues to record in three hours, you can see why we don’t have time for remixing.

Since the show started broadcasting in high definition in 2009, the audio has been broadcast in DOLBY 5.1. This is similar to the way feature films are played in theaters with Left, Center, Right, Left-Surround, Right-Surround, and Low Bass (also called a “Boom”) tracks.

We run two Pro Tools rigs on our sessions. I bring my rig from my studio and we use the installed rig on the Newman Stage as a back-up. After all the recording is finished, I make four back-ups of the digital files and Pro Tools sessions. Three go home with me, one goes home with Alf. The back-up that was made on the Fox rig stays there until the show airs.

Now I head back to my studio with my gear and all the music to complete step 4 – the 2nd half of music editing, or step 4B. I integrate all of the newly recorded cues into the editing session with the music I prepared before the scoring session. Orchestra cues on their own tracks, cues from CDs on their own tracks, the Main Title, End Credits and Logos on their own tracks. I check everything for correct sync, save the final session, then send the whole thing via the Internet to SONY Studios Dub Stage 11 where the episode will be dubbed. Dubbing is step 6, so more on that next time.

Sidebar: A little geek-speak: The show is digitally recorded at 48Khz sample rate, 24-bit word depth, Broadcast Wave files. A typical scoring session generates about 2GB of music files. After I edit the show into its final format and remove all the unused and unwanted takes, the final session size is about 1GB or a little less.

If you have any questions about this or any of the posts in this blog, feel free to leave them in the comments section and I’ll do my best to answer them.

As we watched tonight’s (25 Sept 11) episode my sons and I enjoyed the “flashback” music used for the mass shootings. We are all trying to figure out the name of the piece of music used for the flash back and would be greatful if you could tell us

“Dance of the Knights” – a sequence from the ballet “Romeo and Juliet” by 20th century Russian composer Serge Prokofiev. A great example of SCOURCE because the music starts out as source played by the string quartet, but becomes score as the shooting begins. I appreciate the question.

Thanks for getting back to us so soon. As soon as I saw it was Prokofiev, I should have recognized the genre of music as he also did Peter and the Wolf.

Cheers

What is the name of that classical piece that is played during wayne’s flashbacks where all the shooting is occurring?

See reply to Colin Lloyd, Above. Thanks for the question!

Oh, how I miss cues like “A STING KING SHOCK STING” . . . makes me want to make it my ringtone!

Tell me, does the Sting King still get a ¼” analog copy of the session?

He’s all digital now, but still gets a DAT tape.